Over the last few articles in the Next Wave series, we have been assembling the pieces of a modern, AI-driven finance function from the ground up.

We started by laying a data foundation in an Information Warehouse that we could trust. We used it to generate insights and sharpen our foresight. In the previous article, we added AI Assistants to remove the "interface tax," allowing us to ask questions of our data in plain English and get governed answers instantly.

At this stage, the system is incredibly smart. It can explain variances, identify trends, and answer complex queries. But it still has one major limitation: It creates work, but it doesn't do work.

The previous step was about Conversation (getting the system to understand us), this next step is about Coordination (getting the system to act for us). We are moving beyond simply asking the model to explain a number. We are now defining workflows where the model can act on that number using the same "ReAct" (Reasoning and Acting) loops that developers use to build autonomous software but applied to the governed world of finance.

This isn't about replacing the finance professional. It is about equipping them with a new set of capabilities that closes the gap between insight and action.

The Execution Tax

Getting the answer is only half the battle. Once your AI Assistant tells you, "Margin is down 2% due to a spike in logistics costs," the real work begins. You still have to:

- Email the logistics manager to get the context.

- Update the driver in the Q4 forecast model.

- Re-run the allocation logic.

- Flag the variance for the monthly business review deck.

Right now, that "doing" part is entirely manual. You are the API connecting these systems. You are the glue holding the process together. This is the "Last Mile" of finance. It is an "Execution Tax" that keeps highly skilled analysts trapped in administrative loops, moving data between systems instead of driving strategy. This is where Agentic Workflows come in.

Demystifying the "Agent"

For many in finance, the term "Agent" sounds like sci-fi, or worse, like a "Digital Employee" coming for their job. To cut through this noise, we look to Nicholas Renotte, IBM’s Head of AI Developer Advocacy. His definition is refreshingly simple:

"Agents are really just LLMs with tools."

It isn't a synthetic worker. It is a Brain (the LLM) connected to Hands (Tools like APIs, Email, and ERPs).

- The Brain: Understands the intent ("Update the Q4 forecast").

- The Hands: Execute the technical actions (Query the database, update the cell, send the confirmation email).

When you view it this way, agents aren't scary; they are just a smarter way to connect the systems you already use.

The Reality Check: Workflow vs. Agent

But before we go further down the agentic path, it’s worth acknowledging that complexity has a cost, and most problems don’t need that much of it. The market is currently obsessed with AI agents and while the demos are fantastic, they hide a critical truth: complexity is a tax, and you often don't need to pay it.

As Tobias Zwingmann points out, the choice between a workflow and an agent boils down to predictability:

- AI Workflow (Automation): The steps are predetermined and repeatable. (A -> B -> C). AI models are used as intelligent steps within that sequence (e.g., an LLM classifies an invoice, then the workflow routes it). This is best for tasks requiring high consistency and auditability.

- AI Agent (Autonomy): The goal is fixed, but the steps are chosen at runtime. The agent is given a goal and decides on the fly which tools to use to achieve it. This is best for tasks involving high variability and open-ended reasoning.

The Rule of Thumb: If you find yourself hard-coding the order of actions, a simple workflow is all you need. Don't build an expensive, complex agent if the steps are always the same. Only introduce the complexity of an Agent when the task genuinely requires it to reason and adapt.

Turning Automation into Outcomes: Workflows that Work

Before AI forecasts, before narratives, before autonomy, you need confidence that the close is clean, so that’s where we’ll start.

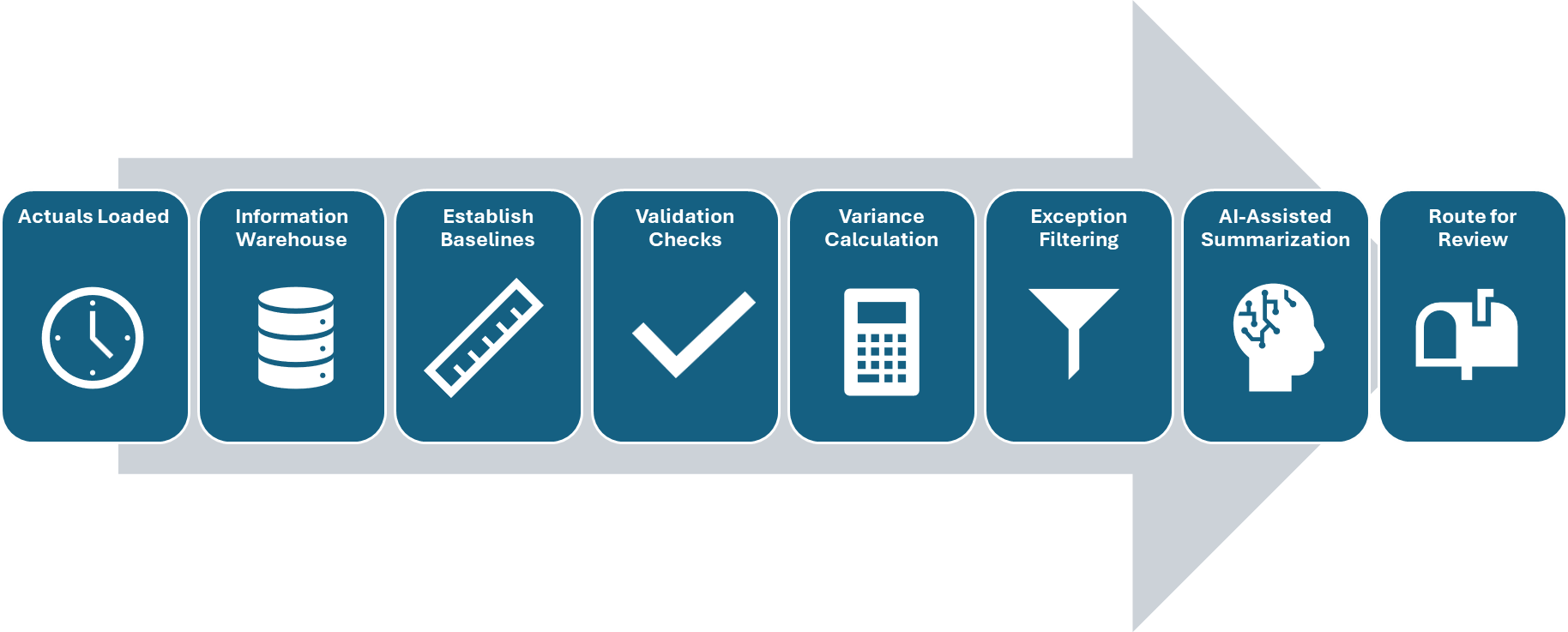

Workflow 1: Close Review and Exception Detection

Trigger: Actuals are loaded to the system on a defined schedule.

Step 1: Establish the comparison baselines

Actuals are compared against two fixed reference points:

- Prior period actuals

- Last approved forecast

These reference points are defined once in the Information Warehouse and reused consistently. There is no dynamic interpretation of what constitutes a valid comparison.

Step 2: Run deterministic validation checks

The system executes rule-based validation logic already embedded in the Information Warehouse:

- Completeness checks to confirm required data is present

- Structural checks to validate hierarchies and mappings

- Threshold checks to identify values outside expected ranges

These checks are deterministic, auditable, and repeatable. No AI is involved at this stage.

Step 3: Calculate variances

Using governed definitions, the system calculates:

- Actuals vs prior period variances

- Actuals vs forecast variances

All calculations follow standard finance logic and can be traced back to approved rules and dimensions.

Step 4: Filter to material exceptions

Variance results are filtered using predefined materiality thresholds. Only exceptions that require attention are retained. Routine or immaterial movements are excluded.

Step 5: Generate a factual summary (AI-assisted)

An LLM is used to convert structured results into a concise, factual summary:

- What moved

- Where it moved

- Whether the movement breaches expected ranges

The model does not infer causes or provide explanations. Its role is limited to summarization.

Step 6: Route for review

Flagged exceptions and summaries are routed to the appropriate owners for review and follow-up.

This use case contains no forecasting, no narrative judgment, and no autonomy. It replaces manual validation and triage with a fast, consistent workflow that establishes trust in the numbers before any higher-order analysis takes place.

Workflow 2: Variance Explanation and Business Review Preparation

This use case begins only after the close is validated based on the previous use case.

Trigger: Close review and exception detection complete.

Actuals are compared against the last approved forecast or plan. This reference point is fixed and governed.

Step 1: Ingest validated exceptions

The workflow consumes only the material exceptions identified in Use Case 1. Non-material movements and failed validations are excluded by design.

This ensures explanations are generated only for numbers finance already trusts.

Step 2: Decompose variances using governed logic

For each exception, the system applies standard variance decomposition logic defined in the Information Warehouse:

- Price

- Volume

- Mix

- FX

- Cost and operational drivers

These decompositions are rule-based and deterministic. The system explains movement within the bounds of the model, not beyond it.

Step 3: Attach relevant context

The workflow enriches each variance with existing, governed context:

- Prior forecast assumptions

- Known business events captured during planning or close

No external inference is introduced. Context is attached, not invented.

Step 4: Generate metric-bound commentary (AI-assisted)

An LLM generates draft commentary that is explicitly constrained:

- Each statement ties back to a specific metric or driver

- Language reflects model outputs and known context only

The system does not speculate on root causes outside the model and does not introduce new explanations. Its role is translation, not interpretation.

Step 5: Populate a locked business review template

The system populates a predefined MBR slide template:

- Charts and tables are fixed and data-driven

- Narrative is inserted only into designated fields

This enforces consistency across business units and reporting cycles.

Step 6: Route for finance review and approval

Draft materials are routed to finance for editing, approval, and final ownership before distribution.

This is still what we would consider a workflow as the sequence never changes and the inputs, logic, and outputs are predefined. AI accelerates explanation and packaging, but it does not choose actions, change logic, or introduce judgment. The system explains known drivers using governed rules. It does not invent causal stories or speculate beyond the model.

Workflow 3: Touchless Forecasting

This use case builds directly on the first two. Now that we’ve performed the close and the variances are validated and explained, we can shift to forecasting.

Trigger: Actuals are loaded and the close review process is complete.

The prior human-approved forecast remains the point of comparison. No forecast is overwritten automatically.

Step 1: Apply governed, rule-based logic first

Before any statistical or machine learning models are run, the system applies existing planning logic from the Information Warehouse:

- Driver-based calculations

- Allocations

- Known contractual or structural changes

This step ensures that what is already known and explicitly modeled is reflected deterministically. AI does not bypass or replace established planning logic.

Step 2: Generate system forecasts where appropriate

Statistical or ML forecasting methods are applied selectively, only to measures and slices where they are suitable.

The outputs are written to a separate System Forecast version. The existing human forecast remains unchanged.

This version separation is deliberate. It preserves auditability and makes comparison explicit.

Step 3: Compare system output to existing forecasts

The workflow calculates deltas between:

- System Forecast vs prior human forecast

- System Forecast vs historical trend

The goal is not to declare a “better” forecast, but to surface where the system disagrees materially with current expectations.

Step 4: Generate structured commentary (AI-assisted)

An LLM generates draft commentary that is explicitly segmented:

- What changed based on new actuals

- What changed due to model logic or drivers

- Where the system forecast diverges from the human forecast

- What areas still require judgment

The model explains differences. It does not decide which forecast is correct.

Step 5: Generate forecast review materials

The system populates a predefined forecast review deck:

- Charts and tables are fixed and data-driven

- Narrative is inserted only into designated sections

This ensures consistency across cycles and business units.

Step 6: Route for human review and approval

Finance reviews the system output, makes adjustments as needed, and explicitly approves the forecast before it becomes the new baseline.

No forecast is committed without human sign-off.

Despite the use of advanced models, this is still what we’d consider a workflow. There are some advanced AI steps in the workflow, but the system does not decide which models to run, which assumptions to change, or when to commit results. Those decisions remain with finance.

Touchless forecasting does not mean decision-less forecasting. It means the system prepares, compares, and explains, so humans can focus on judgment rather than mechanics.

Building for Finance

The biggest gains in finance don’t come from autonomy. They come from disciplined automation. Most of the work that slows finance teams down follows predictable paths, and workflows handle that extremely well.

So why talk about agents at all?

Because there are still classes of problems where workflows break down. Not because the logic is wrong, but because the path itself is not predictable. This is where agents can add value, and where risk appears if they’re built carelessly.

The Constraint: Zero Margin for Error

Nicholas Renotte captures the core issue succinctly: “In certain industries, there is zero margin for error. Who takes responsibility?”

This is the world where FP&A teams operate. The world where forecasts drive decisions and reports inform markets. For finance practitioners, errors don’t just cause rework; they create real consequences.

That constraint doesn’t make agents impossible, but it changes how they must be designed. The goal isn’t autonomy for its own sake, but rather what Nic describes as “superagency.” Systems that extend human capability without removing human accountability.

The Architecture: How to Build Superagency Safely

These workflows handle the knowns. But for the unknown cases where logic cannot be hard-coded, we need to design differently. This brings us to the architecture of safety. If agents are going to exist in finance, they must be built differently from consumer or developer-facing agents. The design principles are not optional.

- Modularity Over Monoliths

Do not build a single, opaque agent that “manages finance.” That is a black box, and black boxes fail audits. Instead, build small, specialized agents with narrow responsibilities like a variance agent that prepares explanations or a close review agent that identifies anomalies.

This way, each step is isolated, each output is inspectable, and if something changes, you swap a component instead of rebuilding the system. Modularity is not just an engineering choice. It is a risk management strategy.

2. Determinism in Actions, Not Creativity

Finance agents should not be creative in what they do. Reasoning can be flexible, but execution must be predictable.

An agent can decide which SOP applies, but it should not invent new ones. When it posts a journal entry, updates a forecast, or drafts a variance explanation, the mechanics must follow approved procedures every time.

3. Human-in-the-Loop by Design

In finance, agents prepare. Humans commit.

An agent can calculate, create first drafts, and assemble context. But approval remains a human responsibility. Not as a fallback, but as a design requirement.

This is how accountability is preserved. You know who approved the outcome, and the system shows how it got there.

Superagency is not about removing humans from the loop. It is about moving them to the point where judgment actually matters.

Conclusion: From Execution to Strategy

When you automate the execution layer, something subtle but important happens. Finance stops being the glue that holds systems together.

Work that once required constant manual coordination for validating numbers, explaining variances, preparing forecasts, assembling decks, and routing approvals no longer consumes most of the team’s time and attention. The system does the preparation, and the humans do the thinking.

This is the real payoff of moving from conversation to coordination. Not smarter answers, but fewer handoffs. Not better dashboards, but less administrative drag. The execution tax shrinks, and highly skilled finance professionals are freed from acting as human middleware.

When the foundation is trusted, insight is explainable, foresight is prepared, and execution is automated, finance can focus on what it was always meant to do. Partner with the business. Challenge assumptions. Shape decisions. Drive outcomes.

This is where AI stops being a productivity tool and starts becoming a strategic enabler.

In the final article of this series, we’ll explore what strategic finance in an AI-enabled world looks like in practice.